Introduction

C++ is used widely for high-performance computing. Mastering pointers is an important step in writing efficient code. In this post, I mention the most useful characteristics of raw pointers with examples.

Here I focus only on raw pointers and assume the code we are working with doesn’t allow smart pointers (unique, shared and weak pointers).

Definition

A pointer is an 8-byte type on a 64-bit machine that holds the memory address of a target object.

int x = 20; // variable declaration

int* p; // pointer declaration

p = &x; // pointer stores address of x

cout<< p <<endl; //0x7ffc52a21a84

cout<< *p <<endl; // 20 : dereferencing with * operator

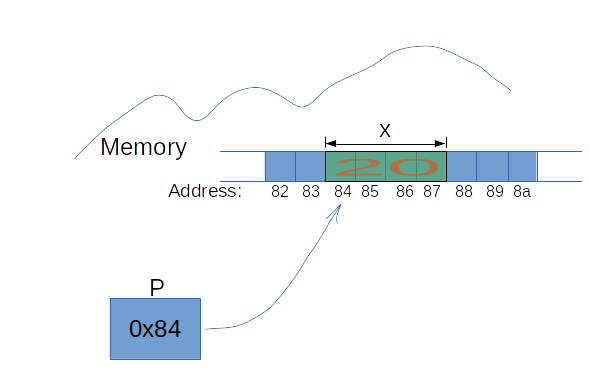

In the above example, p at the beginning is declared but undefined (it points to somewhere we don’t know); it then pointed to x. Roughly, the code is equivalent to the picture below

The pointer holds the memory address of x. Using * operator, the pointer can be dereferenced to get the value of its target.

Memory Allocation

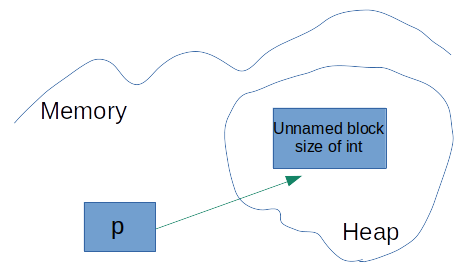

A pointer is usually pointed to dynamically allocated memory on the heap, a scalar

int* p = new int;

or an array

int* q = new int[5];

Delete

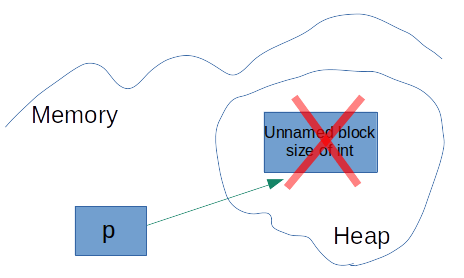

The allocated memory can be deleted (not the pointer itself)

int* p = new int;

delete p; // new int memory now deleted

To delete all elements of the array

int* q = new int[5];

delete[] q; // All elements of array deleted

Note that they are not literally deleted, the memory is marked as free to be overwritten.

Remember that new ends with delete, new[] ends with delete[]. The compiler knows the number of elements of the array created via new[], so delete[] doesn’t need the number of elements.

Do not delete the dynamically created array using delete

int* q = new int[5];

delete q; // Error: only one element is deleted

Do not delete a stack memory that a pointer points to

void f(){

int x;

int* p=&x;

delete p; // Undefined Behaviour: deleting a memory on stack!

}

Do not double delete

int* p = new int;

delete p; // target memory deleted

delete p; // error or undefined behaviour

Null usage

There is no way to know if a pointer is deleted or not associated, therefore, I prefer to point the pointer to nullptr (or NULL for C and older than C++11 compilers) when there is nothing to point to: at declaration and deletion. In this way, some undefined behaviours like double-delete or accessing dangling pointer are avoided.

int* p = nullptr // declaration with null

int* q = new int; // memory allocation

delete q; // removing allocated memory

q = nullptr;

nullptr is type-safe in comparison with NULL. In some cases, compilers confuse the type of NULL with int. We can check if a pointer is null like below

if(p!=nullptr) {...} // C++11 and later

if(p!=NULL) {...} // C and older C++ compilers

if (p) {...} // the same as above lines

It should be noted that making a pointer null after delete hides the double-delete problem explained in the previous section. And it does not affect other pointers pointing to the same deleted memory. Some people don’t like this convention read here.

Dangling pointer

A dangling pointer refers to a pointer that points to memory that has already been deallocated or released, leading to undefined behavior if accessed. Here’s an example:

int* ptr = new int(42); // Dynamically allocate memory and initialize it with 42

delete ptr; // Free the allocated memory

// Now `ptr` is a dangling pointer, as it still points to freed memory

std::cout << "Accessing dangling pointer: " << *ptr << std::endl; // Undefined behavior

To avoid dangling pointers, immediately set the pointer to nullptr after delete:

delete ptr;

ptr = nullptr; // Now it's clear the pointer doesn't point to valid memory

A common case of dangling pointer is pointing to an object that might destroy at some time but the pointer is not aware of it:

int* p;

{

int a=1;

p = &a;

}

std::cout<<*p; // accessing destroyed object

The example above is similiar to when a pointer points to a data member of a destructed class object.

Another example is returning a pointer to a local variable from a function:

int* getLocalPointer() {

int localVar = 42;

return &localVar; // Returning address of a local variable (dangling pointer)

}

int main() {

int* ptr = getLocalPointer();

std::cout << *ptr << std::endl; // Undefined behavior: accessing a dangling pointer

return 0;

}

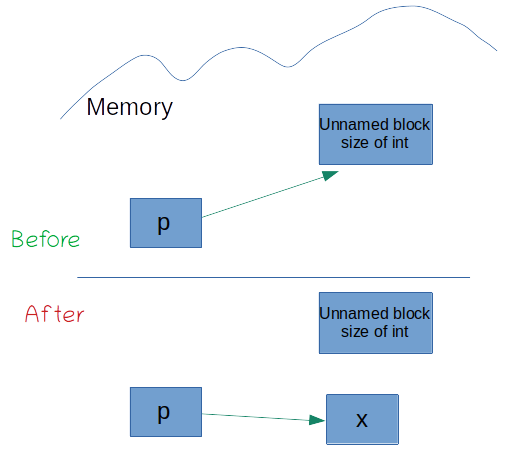

Memory leak

There is no memory management system for raw pointers. Therefore, not deleting the allocated memory of pointer explicitly causes memory leak:

int x;

int* p = new int;

p = &x; // re-pointed but "new int" not deleted

In the above example, new int memory is an island in the sea of computer memory. We could only find it via p but, in the last line, p is pointed to another place, x. So we have a memory leak!

We have to remember to delete the allocated memory and then point the pointer to another target:

int x;

int* p = new int;

delete p;

p = &x;

The same happens if the pointer goes out of scope

// some code here

{

int* p = new int; // p declared and given a new memory

// do some stuff with p

}

// p is destroyed here but new int memory is somewhere not deleted

Again we have to remember to delete it ourself:

{

int* p= new int; // p declared and given a new memory

// do some stuff with p

delete p; // the new int is deleted.

}

A pointer member of a class better be deleted in the destructor

#include<iostream>

using namespace std;

struct A{

int* p;

A(){p = new int; cout<<"p is allocated memory.";}

~A(){delete p; cout<<"p is deleted.";}

};

void f(){

A a; // p is allocated memory.

} // a.p is deleted

There is another situation that memory leaks:

int* p = new int;

// An exception is thrown by some code here!

delete p; // this line is not reached.

A raw pointer cannot handle this, you need to use smart pointers (see this discussion ).

For deleting a memory, the situation gets complicated fast when it is the target of different pointers:

Class Student{...}

Class CourseA{

public:

CourseA(*Student student):Top(student) {}

~A(){// delete Top here?}

Student* Top;

}

Class CourseB{

Public:

CourseB(*Student student):Top(student) {}

~B(){// delete Top here?}

Student* Top;

}

...

{

Student* Jack= new Student();

CourseA* A= new CourseA(Jack);

CourseB* B= new CourseB(Jack);

// delete Jack here, in CourseA or in CourseB destructor?

}

In the above example, three pointers target the same memory location, thus we cannot run delete for all of them as we face double-delete problems explained in the Delete section.

Conventions

If you start working with an existing project, look for pointer conventions in place. If you design a new code put some conventions in place for objects which delete pointers, and the ownership of pointers when they are passed to or returned from functions/objects.

For example, in the previous piece of code, we have to decide which object is the owner, i.e., which one

needs to outlive others. So we delete the pointer in that one and leave the rest as observers.

We can have owner as a type alias for T.

template<class T>

using owner = T;

Now we can have a pointer policy for our code that pointers are defined by owner only when the class containing them is responsible for deleting them.

A simple example that owner acts as a raw pointer:

struct A{

owner<int*> p;

~A(){delete p;}

};

Note that smart pointers, which are introduced in C++11, elegantly address this problem.

Dereference class members

A class member, method or variable, can be accessed via -> operator:

class Person{

public:

string name = "Jack";

}

Person* p = new Person();

std::cout << p->name << endl; // Jack

Pass by pointer vs pass by reference

It is a good practice to pass objects especially the huge ones by a pointer. Instead of copying the whole data, only the pointer is passed:

void DoSomething(vector<int>* v){

/* do something with v */

}

...

auto a = new vector<int>(10000);

DoSomething(a);

I mostly prefer pass by reference as it feels easier to read. However, there is a difference between pass by pointer and pass by reference. When you pass by reference you guarantee that an outer scope always passes valid data to the fucntion. But when you pass data by pointer you may mean the pointer can be null and the function handles it.

When passing by pointer, the pointer itself passed by value.

#include<iostream>

using namespace std;

void f(int* p)

{

*p = 100; // the pointed memory changed

p = nullptr; // p is changed within function not externally

}

int main(){

int* q = new int(0);

cout<< q << endl; // 0x17d8b20

f(q);

cout<< *q << endl; // 100

cout<< q << endl; // 0x17d8b20: q is not changed

}

Constant

A constant qualifier can be added to a pointer in different ways:

const int* p // constant or read-only target, pointer can be reassigned

int* const p // constant pointer cannot be reassigned

const int* const p // both above constraints

The different versions are to constrain a pointer, reduce mistakes, improve readability and help compiler to optimise the code and catch errors.

The target of a constant-target pointer is not necessarily constant:

int a=5;

const int* p = &a; // ok: read-only pointer

a = 10; // ok

*p = 20; // Error:: against "read-only" contract

However, a constant target must be pointed only by a constant-target pointer.

Pointer vs reference member

A reference member of a class must be initialized in the constructor and it cannot be reassigned. However, a pointer member can be reassigned, freed, and null.

Use a reference member if an entity outside of the class controls the lifetime of the member and the entity outlives objects of this class.

#include<iostream>

struct A {

A(int& m_):m(m_){};

int& m;

};

int main(){

int*p = new int(50);

auto a = new A(*p);

std::cout<< a->m; // 50

delete a;

delete p; // p must outlive a

}

Use a pointer member when

- the member lifetime is controlled out of the class and the class handles a null pointer.

- we like lazy initialization of the member, the member needed not to be set up with a constructor.

- the class owns the member and responsible for deleting it.

- the member can be repointed to another target (a reference member cannot be re-assigned).

Arrays and vectors

Pointers can be used to define arrays on the heap

int* p = new int[5]; // dynamically allocated array

int* m = new int[3]{3,1,5}; // C++11: initialize in place

cout<< p[2]; // prints 3rd element

int* q[5]; // array of 5 integer pointers

int arr[5]; // array of 5 integers

int* r = arr; // pointer points to first element of array

cout<< *(r+2); // shows 3rd element of arr

A dynamic 2D array can be created with a pointer-to-pointer type

int **p;

// dynamic array of pointers

// each pointer is a row

p = new int*[3];

// loop over rows

for (int i = 0; i < 3; ++i) {

p[i] = new int[6]; // each row has 6 columns

// p[i] points to dynamic array of int values

}

The elements can be accessed via [] operators

int row=1, column=2;

p[row][column]=3; //

In C++, we have the vector class which has many features and in terms of read-and-write is as fast as a raw array see here. Generally, it’s better to use a vector than a pointer to create an array. But how to dereference a pointer to a vector? many ways:

vector<int> *v = new vector<int>(10);

v->operator[](2); // using operator

(*v)[2]; // dereferencing whole vector first

v->at(2); // using At

v->size(); //Get size

vector<int> &r = *v; // create alias using a reference

r[2]; // index reference

Void pointer

All the pointers (int*, double*, string*, custom_class*) have the same datatype holding the memory address of different targets. So, void* pointer is a pointer the same as others pointing to some memory address but the data type of the target is unknown.

void* p;

int i=10;

double d=1.5;

p = &i;

p = &d;

cout<<*(double*)p; // cast when dereferenced

It is a C language feature to write generic functions. But in C++, knowing void* tricks are not necessary since generic code can be elegantly written with templates, functors and interfaces.

Reading Pointers

Reading pointers, we can understand how data are spread in the memory. We can also check the contiguity of objects. Pointers are printed in hexadecimal (hex) system which includes 16 (or 2⁴) characters {0-9,a-f} .

int* p = new int[5];

cout << p << endl; // 0x55b3ec05beb0

cout << p+1 << endl; // 0x55b3ec05beb4

cout << p+2 << endl; // 0x55b3ec05beb8

cout << p+3 << endl; // 0x55b3ec05bebc

cout << p+4 << endl; // 0x55b3ec05bec0

“0x” represents the hex system. Focusing on the last numbers, {b0, b4, b8, bc, c0}, they increase by 4 units because an integer on the target machine was 4 bytes. In the hex system, we have b8+4=bc and b0+16=c0. Therefore, every 4 integers (or 2 doubles), the second last digit is incremented (b0 → c0).