Introduction

Shared pointers are smart pointers that ameliorate working with dynamically allocated objects. They are invented to avoid memory leaks that raw pointers may bring (see here).

Prerequisites

This post assumes you are familiar with raw pointers, unique pointers and auto keyword.

All the examples are compiled with GCC 10.2 with the flag -std=c++20.

For brevity, some examples miss the headers and main function:

#include <iostream> // For std::cout

#include <memory> // For std::shared_ptr, std::make_shared

using namespace std; // dropping std::

// class definitions

int main(){

// implementations

return 0;

}

Definition

Consider class A

struct A{

int M;

A(int m):M(m){}

};

A shared pointer, pointing to an object of A is defined as

shared_ptr<A> sp1 (new A{5});

or preferably

auto sp1 = make_shared<A>(5);

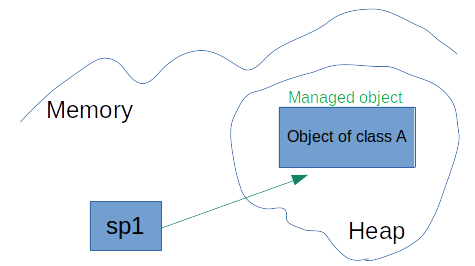

where the new object, new A{}, is created on the heap and sp1 points to it. The object is called the managed object.

sp1 owns the object.

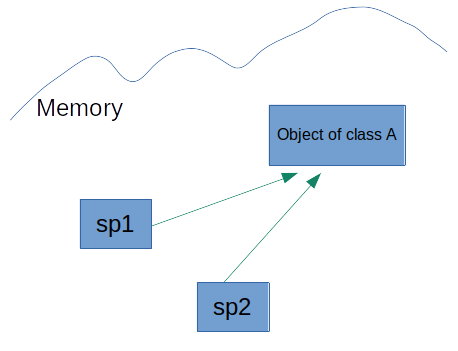

sp1 can share its object with another one

shared_ptr<A> sp2 = sp1;

So the managed object is not re-created or copied, it is pointed by another pointer.

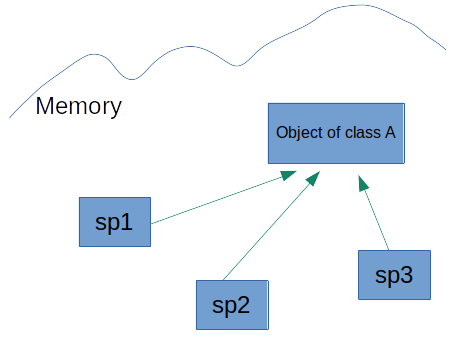

We can share the object with as many shared pointers as we like

auto sp3 = sp1;

A shared pointer can be empty

shared_ptr<A> sp4; // has no managed object.

We can set it later

sp4 = sp3;

Operations

Let’s consider class A again

struct A{

int M;

A(int m):M(m){}

};

A shared pointer supports usual pointer dereferencing

(*sp1).M = 1; // dereference the pointer i.e. get the managed object

sp1-> M = 2; // same as above

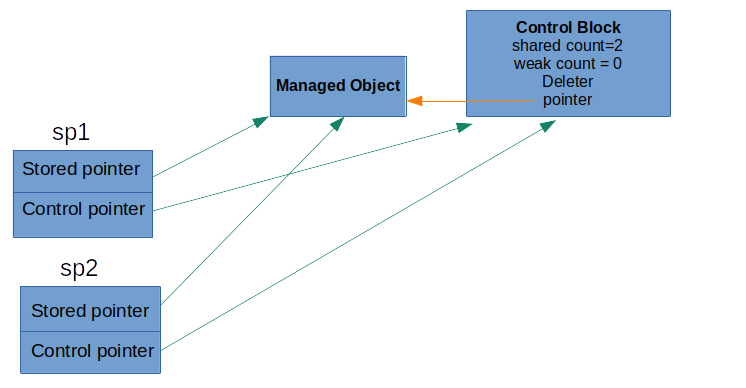

The shared pointer is, in fact, a class which has a raw pointer pointing to the managed object. This pointer is called stored pointer. We can access it

auto p = sp1.get();

cout<< p <<endl; // 0x2070ec0 : memory address of the managed object

Use the stored pointer for accessing and working with the managed object not for modifying its ownership.

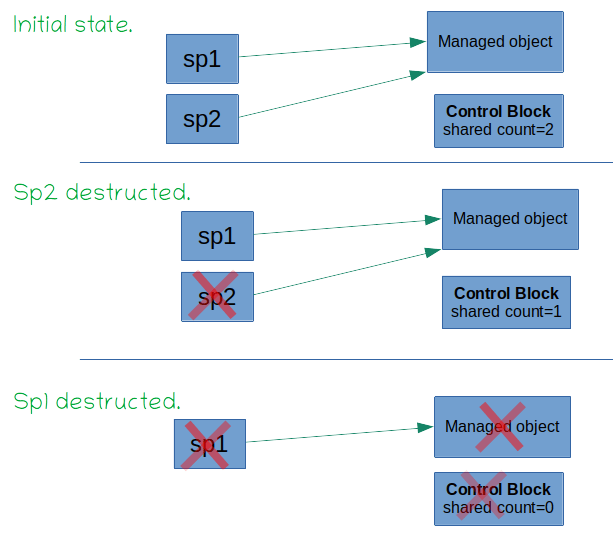

A shared pointer, in addition to the stored pointer, has a second pointer which points to a control block. The control block has a reference counter that memorizes the number of shared pointers pointing to the same object.

At any scope, we can check how many shared pointers point to a managed object

auto sp1 = make_shared<A>(5);

cout<< sp1.use_count()<<endl; // 1 : only sp1 points to the object

shared_ptr<A> sp2 = sp1;

cout<< sp1.use_count()<<endl; // 2 : sp1 and sp2 both point to the object

cout<< sp2.use_count()<<endl; // 2 : both sp1 and sp2 know use counts.

Destruction

If a shared pointer is destructed, the control unit decrements the reference counter:

auto sp1 = make_shared<A>(5);

{

shared_ptr<A> sp2 = sp1;

cout<< sp1.use_count()<<endl; // 2

}

// sp2 is destructed

cout<< sp1.use_count()<<endl; // 1

The managed object will be deleted when the last shared pointer is deleted:

{

auto sp1 = make_shared<A>(5);

{

shared_ptr<A> sp2 = sp1;

cout<< sp1.use_count()<<endl; // 2

}

// sp2 is destructed

cout<< sp1.use_count()<<endl; // 1

}

// sp1 is destructed so is the managed object.

The counter is decremented also if a pointer is detached

auto sp1 = make_shared<A>(5);

auto sp2 = sp1;

auto sp3 = sp1;

cout<< sp1.use_count()<<endl; // 3

sp2.reset(); // sp2 is detached and empty.

sp3 = make_shared<A>(4); // sp3 is reassigned another object.

cout<< sp1.use_count()<<endl; // 1

Pass to function

If the function wants ownership of a shared pointer, we can pass it by value as:

void f(shared_ptr<int> sp){

cout<< sp.use_count()<<endl; // sp is a shared owner.

}

int main(){

auto sp1 = make_shared<int>(5);

cout<< sp1.use_count()<<endl; // 1

f(sp1); // 2

cout<< sp1.use_count()<<endl; // 1 : the shared pointer in f() destructed.

}

Get from a function

A function may return a shared pointer by value

shared_ptr<int> f(){

auto sp = make_shared<int>(5);

return sp;

}

int main(){

auto sp1 = f();

// The shared pointer in the function is dead here.

// But its object is alive and pointed by sp1.

cout<< sp1.use_count()<<endl; // 1

cout<< *sp1;// 5

}

Class Member

A shared pointer can be a class member:

struct Employee{

string Name;

Employee(string name):Name(name){};

};

struct Office{

shared_ptr<Employee> Manager;

Office(shared_ptr<Employee> m):Manager(m){}

};

struct CharityTeam{

shared_ptr<Employee> Volunteer;

CharityTeam(shared_ptr<Employee> v):Volunteer(v){}

};

int main(){

auto Jack = make_shared<Employee>("Jack");

Office office{Jack};

CharityTeam charityTeam{Jack};

cout<< Jack.use_count()<<endl; // 3

}

In the example above, Jack is shared among three pointers. Shared pointers take the memory management out of the way of programmers.

We don’t need to think about deleting a pointer, we don’t need to care which object dies first, or which object outlives others.

Observer function/class

If a function wants just to access the managed object and it doesn’t care about deleting or extending the lifetime of it, we can pass the shared pointer as a raw pointer. A class with similar characteristics can have a raw pointer member.

Performance

Dereferencing a shared pointer has the same performance as a raw pointer (depending on the compiler).

A shared pointer needs two raw pointers. A set of shared pointers which have the same managed object need a control unit. Therefore, the memory that a shared pointer takes is more than a raw pointer and a unique pointer. So, if a vector of a million pointers should be created, probably unique pointers are a better choice.

Creating/deleting/resetting a shared pointer involves some logics: updating the reference counter, checking if it is the first/last pointer and so on. Therefore, we get the better performance to avoid these actions within loops which iterate numerous times (like million times).

Shared pointer, unique pointer or raw pointer

If the program is designed based on smart pointers, then raw pointers are used only to access the managed objects of smart pointers. We must not delete a raw pointer at all.

If an object needs only one owner through the program, and we can imagine the object and the pointer as one entity, then the unique pointer is the way to go. For the high-performance section of the code, unique pointers are better than shared pointers (see the previous section).

Shared pointers can help to code faster in sections of the code that involve high-level programming where we don’t need to think about performance, ownership and lifetime of objects.